Rapid Review

A rapid review of current knowledge and understanding of the demands for and trust in the delivery of Australian public services in regional and remote Australia was undertaken (provided in Appendix 1). This review included local, national and international academic and practice-based literature as well as private sector studies on trust in service delivery and uptake of public services. Synthesising materials provided by the Department and additional published works (including academic and non-academic sources), this review provided key insights into the drivers and components of trust in public service delivery, including the development of the analytical framework. This understanding of trust informed the design and implementation of the qualitative research approaches used in data collection (Component 2).

Co-design workshops to inform research design

The project has embedded a co-design approach with the research team working with APS representatives in the design, delivery and finalisation of the project. Recognising the diversity of experience and insights across the APS, two co-design workshops were held with invited representatives from across the APS. These workshops provided an opportunity for policy, service delivery and data analysts to share insights into regional public service delivery. The strategic workshop focused on the project principles and desired outcomes, providing guidance for the research plan. The technical workshop focused on the case study selection process and relevant data availability across the APS.

Selection of regional and remote communities

An analysis of current quantitative data was undertaken to inform the qualitative research design, with the selection of project study communities based on a quantitative analysis of core community features. This analysis provided important insights into how and where different services are provided, and the level of trust Australians in regional communities have in general (using modelled suburb level data on general trust and trust in Federal Government, modelled using NATSEM’s spatial microsimulation technique). Analysis of available data, together with qualitative insights from co-design workshops, informed case study selection and participant recruitment sample frames, enabling a focused exploration of the drivers behind demands for and trust in Australian government public services.

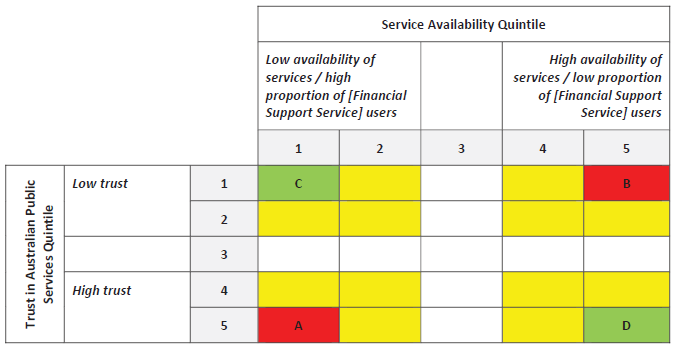

Once the quantitative data was collated and spatially mapped, the ‘off-diagonal method’ was used as an initial basis for selecting communities to study (see Tanton et al., 2016). The aim of the off-diagonal method is to ‘explore the unexpected’. The off-diagonal method identifies those communities that do not have the expected result of one indicator given another (set) indicator. For example, using Figure 5 it would be expected (and hence on-diagonal) that those areas with a low proportion of Centrelink users (generally advantaged areas) would have a high trust in government public services (Box D). Conversely, it is expected (and hence on-diagonal) that those areas that have a high proportion of Centrelink users (generally disadvantaged areas) will have low levels of trust (Box C). The off-diagonals are those where the opposite happens: users have a high level of trust in public services even though they have a high proportion of Centrelink users (Box A), or low levels of trust despite a low proportion of Centrelink users (Box B).

The availability of services was also considered in the off-diagonal selection, however the services where data were available were the number of hospital beds within an 80 kilometre radius (about one hour drive in regional Australia), and the number of school age students. Both these are services provided by State/Territory governments, so the main consideration in the off-diagonal choice was number of Centrelink recipients, which was the only Federal government service provision indicator available.

The level of trust in Government services for communities was not available from the survey on citizen experience administered by PM&C, so a small area estimation method called spatial microsimulation was used to calculate small area estimates of trust in Government services. The spatial microsimulation method has been tested on a number of indicators like poverty and housing stress, and, has been published in high-ranked journals (Tanton, 2011). A full description of the method, including its application for this project and validation of the estimates of trust, is in Appendix 3.

Technical validation of this estimate showed it did not correspond well with estimates of small area generalised trust modelled using the HILDA survey; however expert evaluation of the estimates of trust in government services suggested they were reasonable. While we would not be comfortable using the estimates for other purposes, using them to identify off-diagonal communities, along with other data, was appropriate.

Conducting qualitative and further quantitative research in these ‘unexpected’ communities then allows researchers to identify what factors are associated with demand for and trust in Australian government public services. These factors can then assist policy makers in deciding which service delivery approaches are most effective in enabling service uptake and generating trust in public service delivery.

Modelled small area indicators of trust in Government services using PM&C’s own data, with service availability and use was used to develop this data (see Appendix 2 for how this was calculated).

Once off-diagonal and on-diagonal communities were pinpointed, other considerations were used to finalise the community selections. Other considerations included project logistics (i.e. ensuring sufficient population to attain focus group participants) and a range of contextual factors identified collaboratively with co-design workshop participants as described in Table 1. Therefore the final communities selected might not be wholly off-diagonal (boxes A and B in Figure 5), or on-diagonal (boxes C and D in Figure 5) but rather slightly outside to enable a range of contextual variables to be considered (in the yellow range in Figure 5).

Table 1 Contextual characteristics to consider when selecting study communities

| No. | Additional contextual considerations |

|---|---|

| 1 | Socio-demographic contexts (eg. age, gender, household, employment, education, indigenous proportion, immigration, levels of disability, etc) |

| 2 | Community populations (eg. small, medium and large communities – numbers to be defined) |

| 3 | Economic conditions:

|

| 4 | Australian government public service use

|

| 6 | Current/recent policy interventions and investment:

|

| 7 | Political affiliations (eg. voting, swings) |

| 8 | Remoteness classification |

| 9 | Levels of disadvantage (e.g. SEIFA and IHAD) and wealth estimates |

| 10 | Geographic differences (eg. North/South, East/West, within states where differences common) |

Data to inform these additional considerations were sourced from a range of government agencies including the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (eg. Census data), PM&C (Citizen Experience Survey), the Department of Infrastructure, the Department of Human Services (eg. Complaints to DHS, if available) and other sources (e.g. AURIN, data.gov.au, etc). For this analysis ABS localities in regional areas were used (part of the ABS Urban Centre and Locality geography). These equate to towns in regional Australia.

A minimum of two study communities was identified for each State and Territory (excluding the ACT). To preserve privacy and minimise the risk of communities being adversely affected by their inclusion in the study, the final identity of study communities selected will only be known by the UC research team. Communities are de-identified. Figure 6 shows the indicative numbers (not locations) of community selections included in the study.

It is important to recognise that this project is designed to be an iterative approach where each component constantly feeds into each other as described in Figure 6. As such, qualitative and quantitative analyses are embedded throughout the project to inform project design, delivery and analysis. For example, where qualitative analysis identifies an issue affecting trust (eg. perceived poor access to services), this finding can be empirically verified using quantitative analysis.