This section focuses on reviewing the findings of specific APS survey research which has sought to evaluate public perceptions of the quality of Australian public service production. Four sources of data are considered including key findings from: 1) PM&C’s Citizen Experience Survey; 2) Telstra’s 2017 Connected Government Survey; 3) the Digital Transformation Agency’s (DTA) GovX team’s recent work on “common pain points” experienced by the public in their interaction with government services; and 4) the recent 2019 review of business.gov.au in the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (DIIS). The findings are integrated in response to two questions: what do Australians think about the services they receive? And, do Australians have preferences in terms of delivery systems?

What do Australians think about the services they receive?

Preliminary findings from the Citizen Experience Survey undertaken by PM&C indicates that when comparing experiences of people in regional and remote areas compared to those in urban areas (i.e. major cities), there are similar satisfaction rates with public services, and similar levels of effort to access and receive public services, but only 27 percent of regional Australians trust Australian government public services, compared with 32 percent of urban citizens. These low levels of trust, despite high levels of satisfaction, highlight that government performance (where here trust in public services is a proxy) is only one factor driving citizen’s confidence in government (Sims 2001). Rather, government performance – and with it citizens trust in public services, trust in government and trust in democracy – is the result of complex interacting processes which reach beyond service delivery, including: policy and program design which attempts to reconcile diverging interests and balance numerous political and resource constraints; media framing of government performance; and, the behaviour of political elites (Sims 2001; Stoker et al. 2018b). Box 1 presents an overview of the key findings from the Citizen Experience Survey demonstrating that we cannot rely on the proposition that trust is an outcome of citizen expectations of a service and satisfaction with a service (see for example Morgeson 2012; OECD 2017).

Nonetheless, it is also evident that through the use of user-first principles of service design it is possible to identify common problems in the public’s experience of service. The DTA GovX team (2019), for example, has conducted a “common pain points” project with target groups of citizens which analyses “how people interact with government as they experience different events in their life, such as looking for work or caring for a loved one”. The findings provide a set of action points for improving the quality of the service experience (see Box 2). We will revisit these in the next section.

Box 1. Key findings from the Citizen Experience Survey

- Satisfaction (54%) with service outcomes is higher than trust (29%).

- 60 per cent of respondents are “non-aligned”; neither “trusting” or “distrusting”.

- Service experience during significant life events affect trust in the APS.

- Personal individual service delivery experiences drive overall trust.

- Australians trust the APS to use their data responsibly, but don’t trust them to store it securely.

- Trust is lower in regional (28%) in contrast to urban (34%) areas.

Do Australians have preferences in terms of delivery systems?

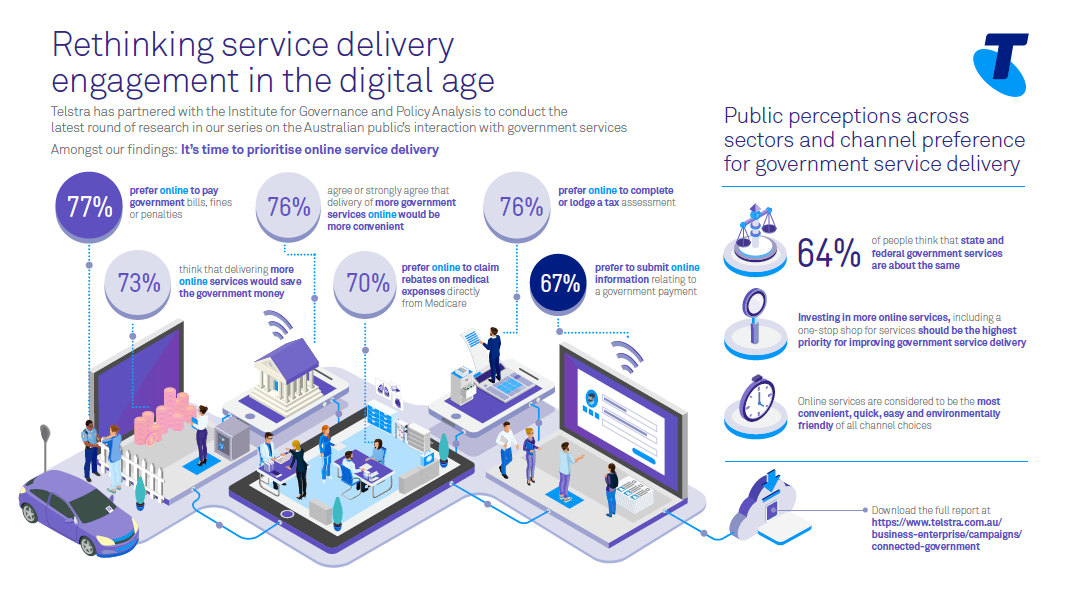

We recently conducted a national survey for Telstra on Australian attitudes towards digital public service production[11] and we found that: there is a sustained willingness amongst the Australian citizenry to use online services and a preference for on-line services over other delivery channels; the public sector is still perceived to be behind the private sector on key measures of service delivery but Australian citizens want digital services and don’t really care whether they are delivered by public or private sector organisations; confidence in government to deliver effective public policy outcomes is very low but there is a belief that digitisation could be used as an effective tool for rebuilding trust with the citizenry; and, the vast majority of the Australian public endorsed and expected the APS to engage in experimentation and service innovation (see Figure 1). Table 2 presents a snapshot of satisfaction drivers by channel in the Department of Human Services. In contrast, it shows that “face to face” channels remain the most effective driver of citizen satisfaction; although it is equally evident that the mix of channels is important to respond to the different needs of citizens.

Box 2. Common pain points in government-citizen interaction

- Lack of proactive engagement from government with the user

- Difficulty finding the right information, at the right time, in the right context

- Services hindered by the complexity of government structure

- Uncertainty about government entitlements and obligations

- Not meeting service delivery expectations

- Users being required to provide information multiple times

- Inconsistent & inaccessible content

- Complexity of tools provided by government

Source: DTA GovX 2019

Figure 1. Public perceptions across sectors and channel preference for public service delivery

In the first quarter of 2019 a review was conducted of Business.gov.au in DIIS.[12] The purpose of the review was to assess whether the needs and aspirations of small and family business owners are being supported effectively by business.gov.au and to provide recommendations on how the service experience could be enhanced. The recommendations draw on quantitative surveys of small business users conducted by the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science in 2013, 2015 and 2017 (Winning Moves, 2017). The research provides us with some key lessons for the public service system as a whole in relation to digital service delivery:

- User centred design is critical to delivering a high quality service experience.

- Small business owners want a trusted, one-stop shop to access the government information and assistance that they need. It should not mirror government internal structures (federal, state, local) and content should not be dispersed across multiple agencies, platforms and technologies (various applications and websites). Hence digital services should have a clear vision and scope.

- Small business owners expect on-line services to be accessible from a range of devices and easily navigable (functionality).

- Small business owners desire relevant and practical content that is tailored for their personal and user journey (personalisation).

- Appropriate channels of communication should be used to heighten awareness of the service. Although satisfaction with business.gov.au is high (93%), awareness is low (44%). Intermediaries (in this case accountants, bookkeepers, business advisers, and industry and professional associations are key points of contact for small business) can be better leveraged to push out relevant information that meets user needs.

Table 2. A snapshot of satisfaction drivers by channel in the Department of Human Services

| Centrelink | Child support | Medicare | ||||

| Driver | Face to face | Phone | Online | Mobile Apps | Phone | Face to Face |

| Perceived quality | 79.9 | 74.9 | 70.7 | 78.8 | ||

| Personalised service | 83.7 | 80.3 | N/A | N/A | 81.2 | 91.5 |

| Communication | 83.1 | 80.5 | 77.3 | 82.2 | 82.9 | 92.6 |

| Time to receive service | 71.5 | 51.7 | 71.6 | 78.5 | 58.7 | 71.1 |

| Fair treatment | 91.5 | 90.9 | N/A | N/A | 85.6 | 94.4 |

| Effort | 77.9 | 67.5 | 68.4 | 77.1 | 70.4 | 83.2 |

| KPI result | 81.2 | 74.1 | 72.0 | 79.0 | 79.0 | 86.1 |

Source: Senate Estimates July 2018 to February 2019

*mobile Apps as a channel added from October 2018

n.b. work is underway to include the online channels for Child Support and Medicare

Summary

The data presented in this section is in keeping with the core findings from the secondary literature on the take-up of digital public services. For example, Carter and Belanger (2005) found that trustworthiness of e-government services influenced service uptake; and, Lee and Turban (2001) observed that citizens need to trust both the agency and the technology.

The broader literature on public service delivery in regional areas does provide some guidance for further consideration of the potential to improve trust and the delivery of public services in regional Australia. Roufeil and Battye’s (2008) review of regional, rural and remote family and relationships service delivery highlights some significant challenges, but also points to the potential enabling factor of good trust between service providers and the communities – better service delivery is possible. They also highlight the importance of bespoke place-based delivery, that services cannot be delivered in rural areas like they are in urban areas as an important consideration (see also RAI 2015 who also emphasises flexibility in policy delivery and effective multi-level government governance arrangements).

This observation also suggests that it has become imperative for the Commonwealth Government to join-up social and economic development programs and services around regional development hubs to target and alleviate increased marginalisation.

[11] Evans, M. and Halupka, M. (2017), Telstra Connected Government Survey: Delivering Digital Government: the Australian Public Scorecard, retrieved 19 May 2019 from: https://insight.telstra.com.au/deliveringdigitalgovernment .

[12] Small Business Advisory Group Report (2019), Unlocking the Potential of Business.gov.au, Canberra, DIIS.