‘Line of sight’ is achieved when there is a clear accountability route between delivery in the community (outcomes) and the high-level goals the agency has set itself (see Figure 8).10 The evidence here clearly demonstrates that public services are a creative space for building trust with the citizen but there appear to be systemic barriers to the achievement of ‘line of sight’ in practice. Two key strategic questions come to the fore. What can an agency do to achieve ‘line of sight’, lift performance and link Canberra better to the front-line and the front-line better to Canberra? And, what can the entire APS do (more generally whole-ofgovernment) to achieve line of sight, lift performance and link Canberra better to the frontline and the frontline better to Canberra?11

The development and implementation of a common service delivery framework for APS agencies with service delivery functions such as this one would be a useful starting point. This would also require an outcomes-based approach which is generally considered more likely to motivate those who will achieve the results sought: frontline workers and citizens themselves. This is the key to lifting service performance.

One of the difficulties with performance targets is that if they are not linked explicitly to outcomes through line of sight they can create a culture that works exclusively to meet targets without regard for the broader goals and the system in which government operates, resulting in the phenomenon of hard working organisations which achieve targets in the short term but which achieve less and less over the long term. By re-focusing on a small number of measurable and verifiable outcomes in different areas of policy endeavour, agencies can stay motivated on making progress.12

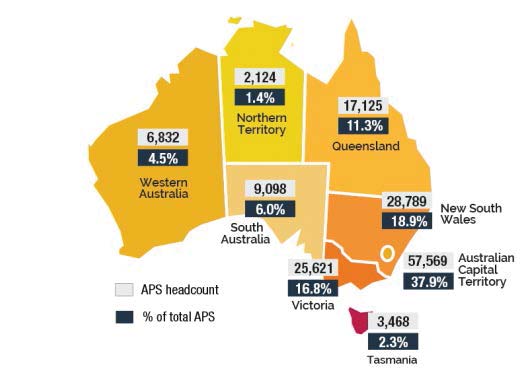

Then there is the question of how APS delivery agencies can achieve the degree of service integration that citizens would like to experience. The APS’s significant regional footprint provides rich opportunities in this regard (see Figure 6.2).

This could include the development of a regional institution aimed at:

- enhancing community engagement and inclusion;

- improving service culture; and

- achieving service integration (e.g. Services Australia Regional Service Centres).

Services Australia Regional Service Centres could have the following features:

- a hub and spokes partnership model with shared risk and investment across sectors;

- based at the regional level with spokes into local governance;

- operate on a place-based approach;

- a co-design approach would be deployed to ensure regional and community ownership;

- focused on delivering key well-being outcomes through a user-first approach with a mandate to upskill regional communities; and,

- through which APS services could be integrated through a whole-of-government approach.

(Source: APS Statistical Bulletin 2016-17 – data tables, Table 7a)

Alternatively, Regional Support Centres could be organised around the implementation of regional programs aimed at addressing specific regional problems in social and economic sustainable development but using the same operating features. Victoria’s “Collaboration for Impact” provides a useful model in this regard.13

It should be recognised, however, that this would a radical departure from orthodoxy for many APS agencies. Australian public servants are measured and rewarded for success in refining processes (for instance, better consultation, less regulation, the monetisation of benefits), or for helping to produce outputs (more nurses, more qualifications achieved, more sustainable businesses) or for managing inputs (a bigger budget for recycling, a 10 percent saving in administrative costs) but are very rarely, if at all recognised for the contribution they make to achieving outcomes. So, there will be significant implications for performance measurement and management arising from this recommendation. Regardless of the model, permanence and cultural authority within the broader system of Australian governance will be important to avoid past failures.

It was also observed by our workshop participants that there is the potential here for savings. There is considerable waste and duplication within the existing siloed system; but, it has never been properly costed suggesting the need for the Department of Finance to undertake a productivity review of the existing service delivery system.

The budgetary system will also need to be refined to encourage greater collaboration between service delivery agencies. One way of achieving this would be for the Expenditure Review Committee to only accept collaborative New Policy Proposals from service delivery agencies.

The New Zealand Government has been much lauded for achieving significant progress in this area, firstly in consequence of reforms to cope with the Global Financial Crisis and then latterly to ensure more agile, and responsive service delivery.14 The latest Kiwis Count Survey shows New Zealanders have increasing trust in the public service with satisfaction with the provision of services at a record high.15 The New Zealand case should be closely monitored for progressive lessons.

10 See: Evans, M. and McGregor, C. (2018), Mandate for change: Towards an integrated service delivery model, Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, for an attempt to achieve this approach in the APS.

11 See: Productivity Commission New Zealand (2017), Measuring and Improving State Sector Productivity, Issues Paper, July 2017; PwC (2013), Improving public sector productivity through prioritisation, measurement and alignment, December.

12 See Jake Chapman’s work on the use of targets, notably in: Chapman, J. System Failure: why governments must learn to think differently. London. Demos. 2002 and Bentley T and Wilsdon J (Eds). The Adaptive State. London, Demos, 2003.

13 See: https://collaborationforimpact.com/impacting/initiatives/ (retrieved 20 November 2019).

14 See: https://ssc.govt.nz/our-work/reforms/ (retrieved 20 November 2019).

15 See: https://ssc.govt.nz/our-work/kiwis-count/ (retrieved 20 November 2019).